Member-only story

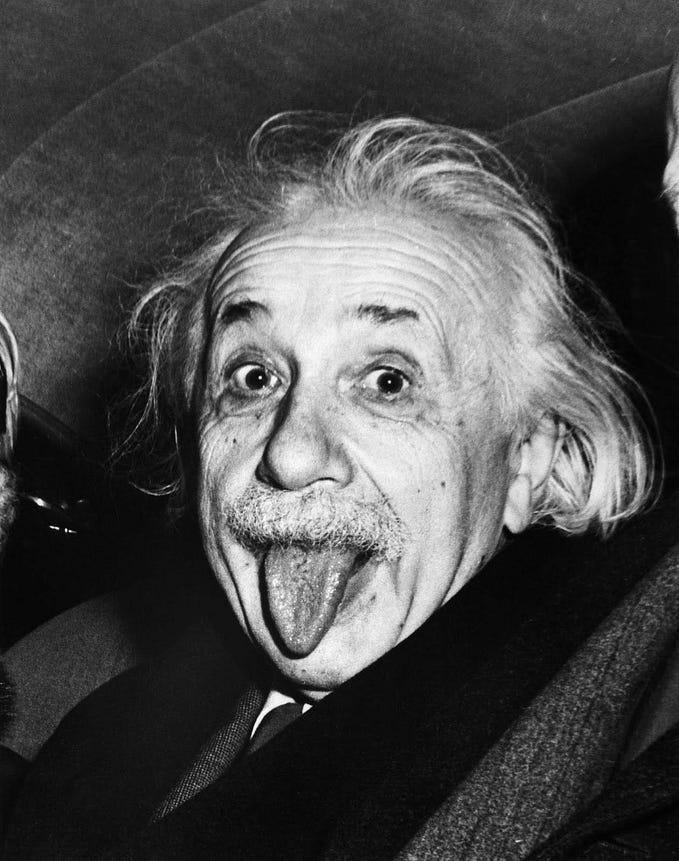

Cicero’s On the Nature of the Gods, and why the Stoics got it wrong — part I

Philosophies of life have a lot in common with religions. Up to a point. Both systems of thought comprise, at a minimum, two components: a metaphysics and an ethics. The metaphysics provides adherents to a given system some notion of how the world works; the ethics gives them guidance on how to live in the world. So if you are a Stoic, for instance, you accept the metaphysical notion of a universal web of cause-effect (which the ancient Stoics called “god”), as well as that everything that exists is made of matter. Ethically speaking, you are on board with the idea that virtue is the only true good, and that we should behave as citizens of the world (cosmopolitanism). If you are a Christian, by contrast, metaphysically you accept that the world was created by an omnipotent god who exists outside of time and space, and ethically you agree that we should help others and offer the other cheek even to our enemies.

One major difference between philosophies of life and religions, however, is that the founders and early contributors to philosophical schools are not regarded as gods, and what they wrote is not scripture. We are free to change things that we think no longer stand up to scrutiny. That’s why, for instance, I suggested that the notion of a Stoic god interpreted as a cosmic living organism endowed with reason (the logos) is untenable in the light of modern science, and hence ought to be dropped. Of course, if we start dropping and replacing components of a coherent philosophical system there may be a legitimate question as to whether what we are left with is, in fact, “Stoic” in any reasonable sense of the word. Good question, but not the one I wish to address today.

Instead, we are going to look at book II of Cicero’s De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of the Gods). Why? Because it presents in detail the Stoic arguments for the existence of a god conceived as a living creature coincident, spatially and temporally, with the universe itself. We will see why these arguments were reasonable two millennia ago, when they were articulated, but no longer are. Which is a good example of what the ancients got wrong, and that we modern Stoics ought to change. Throughout the following, keep in mind one of my favorite quotes from Seneca: