Member-only story

What philosophers think, 2020 edition

Philosophy, contra popular opinion (even among some philosophers) makes progress. I have written a whole (free!) book (summarized here) about how that works. The basic idea is that philosophy, unlike science, is in the business of discovering, exploring, and refining conceptual landscapes defined by the questions in which philosophers are interested in.

For instance, if the issue is the articulation of frameworks for thinking about moral philosophy, the corresponding landscape includes a number of peaks that identify virtue ethics, deontology, utilitarianism, ethics of care, etc.. Progress then consists of first of all identifying new peaks in the landscape. Utilitarianism, for example, did not exist until Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill put it on the map in the early 19th century. Subsequently, progress consists of exploring and refining a given peak: Mill’s version of utilitarianism was more sophisticated than Bentham’s, and various modern varieties of the philosophy are more sophisticated than Mill’s.

But do we have any empirical evidence that this is the way philosophy works? Yes, from two major sources. One, of course, is the history of philosophy itself, as recently argued by my colleague Peter Adamson. Another is to periodically survey professional philosophers about what they think of the major questions in their field and see if the results are compatible with the conceptual landscape model.

The latter approach has been pioneered by David Bourget and David Chalmers, who first published their results in 2013, and have recently updated their data. I commented on their first paper here, and I’d like to highlight some of the results of the more recent survey in this essay.

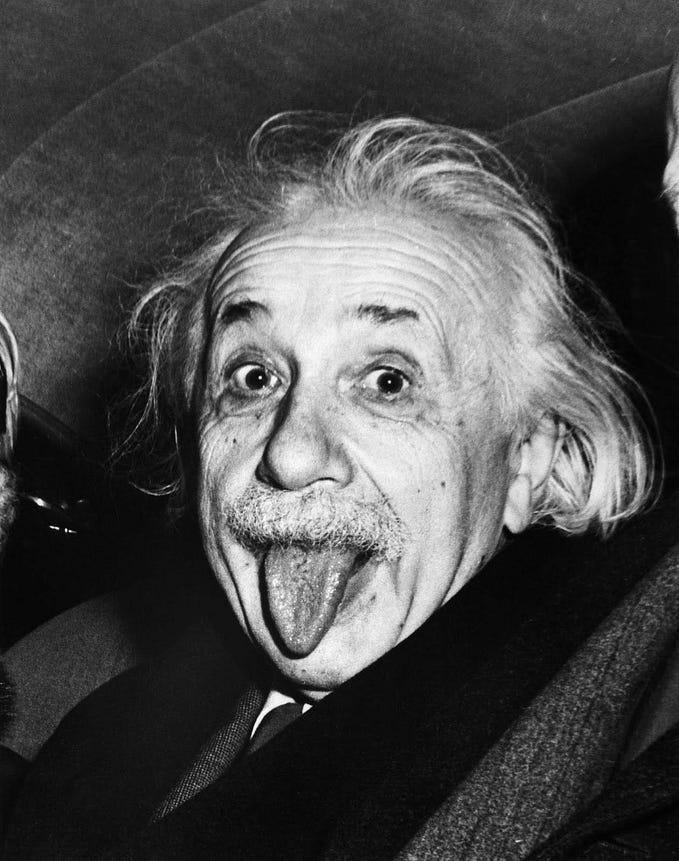

The major thing you will notice is that there is no unanimity on pretty much any of the big questions, something detractors of the field take as evidence that philosophy does not, in fact make progress. But that criticism is based on a misconceived analogy with science. (And even there, it isn’t always the case that scientists actually agree on what’s going on, including in the alleged queen of the sciences, fundamental physics!) In science it makes some sense to ask whether a theory, say, Einstein’s general relativity, is “true” or not, meaning whether it corresponds with the way the world works. Even…